The June 18 Greenbelt City Council worksession covered the issue of ranked choice voting (RCV). Greenbelt Election Advisory Board Member Nicole Shyong presented the principles underlying the proposal, what its potential application could look like and its possible benefits and pitfalls. Shyong also addressed any outstanding questions and the topic of a potential referendum on the question of whether to implement it.

What Is Ranked Choice?

RCV is a system where voters vote in order of their preferences for a given set of candidates. In Greenbelt’s current system (called plurality voting), voters select up to seven choices out of a list of candidates without any distinction among them in terms of whom they would most prefer to see in office. With ranked choice, voters select whom they prefer the most as a first choice, which one they prefer slightly less as second, next most preferred as third, and so on.

This would not be as dramatic of a change as plurality-to-ranked choice transitions typically are since Greenbelt voters already have the chance to select more than one choice. However, in our current plurality system, voters will sometimes not vote at all for their second-most-preferred candidate in order to increase the chances for their favorite winning. This including or excluding of certain candidates is a way of implicitly signaling the voter’s ranking of candidates. Ranked choice explicitly allows the expression of preference.

Instant Runoff

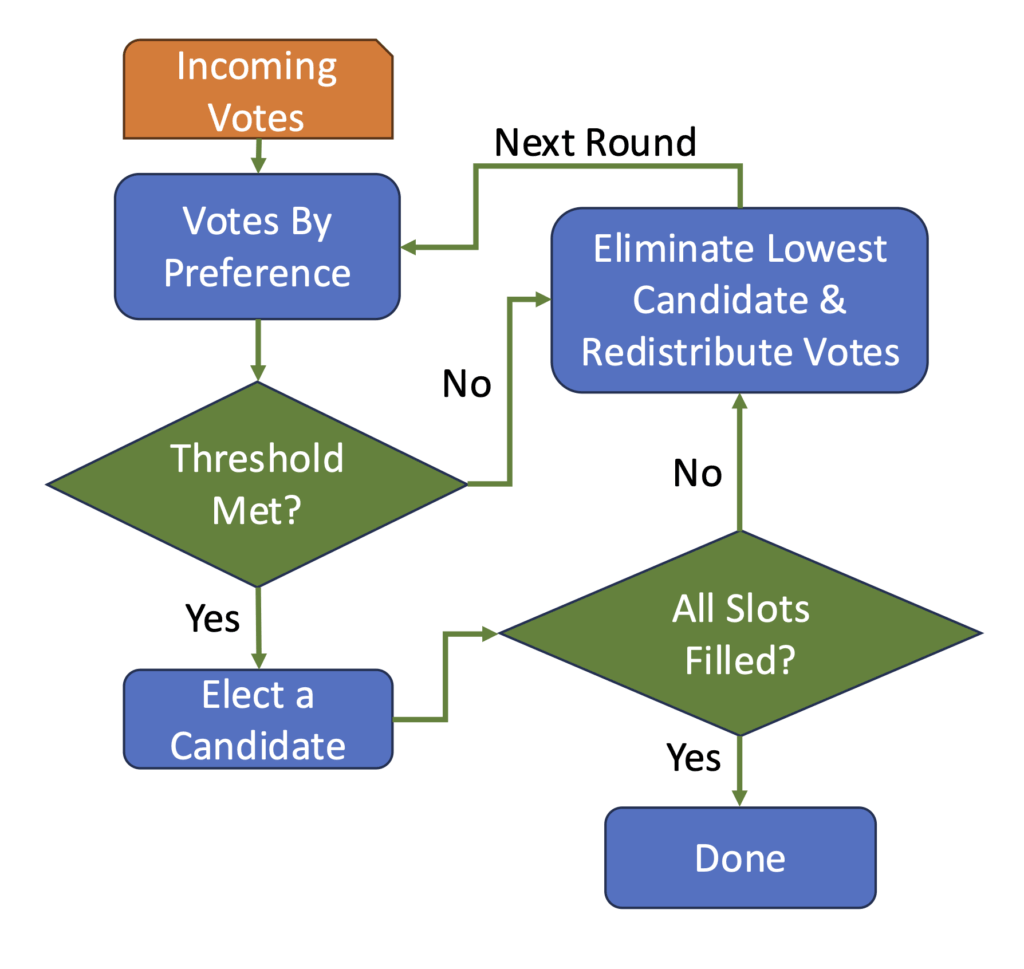

There are many ways a ranked choice system can be implemented, and the one under discussion with council is a version commonly known as instant runoff. At a single election, voters rank their choices as they see fit. Ballots are collected and a threshold of victory (as a percentage of votes cast) is determined based on the size of the electorate. For example, if the threshold is 30 percent, a candidate must have 30 percent of the voters pick them as their first choice.

Candidates who reach the threshold of votes win outright in this first round. If no one wins or all seats are not filled, instead of going back to the electorate for a runoff, the candidate who received the fewest votes is eliminated and the already-cast preferences for the remaining candidates are tallied.

The voters whose first-choice candidates were eliminated (either by being elected or eliminated) have their votes redistributed to their respective second choices (there are a number of options for how this is done). The votes are tabulated again and whichever candidates reach the threshold are elected. Rounds continue until all slots are filled. In practice, only a few rounds or a re-establishment of threshold are required to complete the process – and no second election is required, potentially saving time and money.

Visualizing RCV

The League of Women Voters created a helpful graphic, which we modified slightly, to illustrate the decision-making process that goes on with ranked choice voting. The loop through the votes is repeated to work through the preference scores until all seats are filled.

Minnesota and Monotonicity

Linked to the presentation to council is a helpful explanation by Minnesota Public Radio simulating ranked choice voting via instant runoff (youtube.com/watch?v=lNxwMdI8OWw). The clip illustrates the process using different-color sticky notes coupled with clear, if simplified, narration but, unlike Greenbelt, fills only one opening.

One issue, however, that came up during the worksession and in the simulation is that in a ranked choice election under certain circumstances, a candidate can be ahead in the first round of voting and still lose, depending exactly how candidates are eliminated and votes are redistributed.

This potential reversal is related to a mathematical property called monotonicity. This means the outcome of a system either stays going in one direction, like an escalator going up (monotonic) or goes up and down like a roller coaster (not monotonic). In a voting system, monotonic would mean that a candidate ahead in one round would continue to be ahead in the next: but RCV systems are not monotonic. (See box).

The lack of monotonicity raises the possibility that a candidate might gain more support depending on which round they make it to and a candidate who was initially ahead could then lose. A community member alluded to this possibility and noted that it could lead some voters, especially those without much experience, to become suspicious of the process and lead to demoralization or even allegations of fraud.

Education, Transparency

There were a number of perspectives voiced during the council worksession but one throughline among proponents and detractors alike is that education and greater transparency must be central to any proposed change to the current system of voting. Changes proposed, be they to do with the size of districts or the manner of voting, will likely draw different reactions from different groups of voters and community members, and come with complications and nuances not immediately observable to the average person. As such there was consensus in the meeting that such changes should be made as clear as possible and subject to democratic determination.

Cathie Meetre assisted in the preparation of this story.